- AI

- Technology

Key Concepts for Working with AI

The essential concepts you need to understand to start working with AI tooling: models, tokens, agents, prompting, context, and the Model Context Protocol.

This is part two of my AI in 2025 series, where I covered what AI actually is and isn’t. In this article, I’ll cover the key concepts everyone working with AI tooling should understand. Each deserves more than I can cover here, but after reading this post, you’ll be ready to start experimenting with AI workflows and diving deeper.

Models

Starting off with one of the most basic concepts: models. What is a model anyway?

In the context of AI, a “model” is the trained artifact that does the actual work. It’s a massive file containing billions of numerical parameters (weights) that were learned from training data. When you “use ChatGPT,” you’re sending text to a model that processes your input and generates a response based on those learned patterns.

Different models have different capabilities, sizes, and specializations. GPT-4, Claude, Llama, Gemini: these are all different models with different strengths. Some are better at coding, some at reasoning, some at following instructions. The model you choose matters.

Local vs Remote Models

Models can run in two places: on your machine (local) or on someone else’s servers (remote).

Remote models are what most people use. You send a request to an API (OpenAI, Anthropic, Google), their servers run the model, and you get a response back. The upside: you get access to massive models without needing expensive hardware. The downside: you’re paying per use, your data leaves your machine, and you’re dependent on someone else’s infrastructure.

Local models run entirely on your hardware. Tools like Ollama or LM Studio let you download and run open-source models on your own machine. You can find thousands of these models on Hugging Face, which has become the de facto hub for open-source AI models. The upside: privacy, no per-request costs, works offline. The downside: you need decent hardware (especially GPU memory), and local models are typically smaller and less capable than the big remote ones.

Temperature and Generation Parameters

When you call an LLM, you’re not just sending a prompt. You’re also sending parameters that control how the model generates its response.

Temperature is the most important one. It controls randomness. A temperature of 0 makes the model deterministic: it picks the most likely next token every time, giving you consistent but sometimes boring outputs. Higher temperatures (0.7-1.0) introduce more randomness, making outputs more creative but less predictable. For coding tasks, lower temperatures work better. For brainstorming or creative writing, higher temperatures help.

Other common parameters:

- Max tokens: Caps the response length. Useful for controlling costs and keeping outputs focused.

- Top-p (nucleus sampling): An alternative to temperature that limits the model to considering only the most probable tokens. Usually you set one or the other, not both.

- Stop sequences: Strings that tell the model to stop generating. Useful for structured outputs.

Most AI tools handle these for you, but when you’re using APIs directly or fine-tuning behavior, knowing these exist matters.

Both remote and local models measure usage in tokens, which brings us to the next concept.

Tokens

Tokens are the fundamental unit of text that LLMs work with. They’re not words, not characters, but chunks of text that the model has learned to recognize as meaningful units.

A token might be a whole word (“hello”), part of a word (“ing”, “tion”), a single character, or even punctuation. On average, one token is roughly 3-4 characters in English. A short sentence like “I love programming” might be 4-5 tokens depending on the tokenizer. A longer word like “tokenization” often gets split into multiple tokens.

Why does this matter? Two reasons: billing and context limits.

Tokens are how you’re billed for API usage. But more importantly, they define the model’s context window, the total amount of text it can “see” at once. This includes your prompt, any context you provide, and the model’s response. A 128K token context window is roughly the length of a novel, though the exact word count varies by language and content.

Sounds like a lot, right? It fills up faster than you’d expect. A medium-sized codebase can be 50K+ tokens. A few documentation pages, some error logs, and your conversation history? You’re at the limit. When you hit it, the model either refuses to respond or starts “forgetting” earlier parts of the conversation. This is one of the most common frustrations for new users: the model suddenly loses context on something you discussed five messages ago, and you realize you’ve blown past the window.

Good AI tools manage this automatically by summarizing or dropping older context. But when you’re working directly with APIs or debugging weird behavior, context limits are often the culprit.

Here’s what typical API costs look like for a simple exchange (around 150 tokens in, 150 tokens out):

| Model | Price per 1M tokens (input/output) | Cost for ~150 token exchange |

|---|---|---|

| GPT-5.2 | $1.75 input / $14 output | ~$0.0024 |

| Claude Sonnet 4.5 | $3 input / $15 output | ~$0.0027 |

| Claude Opus 4.5 | $5 input / $25 output | ~$0.0045 |

| GPT-4 | $30 input / $60 output | ~$0.0135 |

Prices are approximate and change frequently. Check the provider’s pricing page for current rates.

Notice something odd? GPT-4, an older model, is roughly 5x more expensive than the newer ones. This isn’t a typo. Newer models are often more efficient, trained on better infrastructure, and priced to compete. Don’t assume “older = cheaper.” Always check current pricing before committing to a model.

What Does Real Usage Actually Cost?

A single prompt exchange is cheap. But what about a real work session?

A typical hour of active AI-assisted coding might involve 50-100 exchanges, with prompts getting longer as you add context. Call it 5K-10K tokens input and 10K-20K tokens output per hour. With Claude Sonnet 4.5, that’s roughly $0.15-0.35/hour. An intense day of coding with heavy AI usage might run $2-5.

Agents are more expensive because they chain multiple calls together. A single “refactor this module” request might trigger 10-20 API calls as the agent reads files, plans changes, and applies edits. That one task could cost $0.50-2.00 depending on the model and codebase size.

These costs are low enough that most individuals and teams don’t worry about them. But if you’re building a product that makes API calls at scale, the math changes fast. A thousand users each making 100 requests/day adds up.

Every prompt you send and every response you receive costs tokens. Understanding this helps you write more efficient prompts and avoid unexpected API bills.

Agents

You’ve probably heard “AI agents” thrown around a lot. Let’s cut through the noise.

An agent is an LLM that can semi-autonomously use tools, follow plans, and take multi-step actions. Instead of responding to a single prompt and stopping, an agent operates with goals, context, and constraints. You give it a task, and it figures out the steps to complete it.

The key difference from a regular chatbot? Tools. An agent can read files, run terminal commands, search the web, call APIs, and modify code. It’s not just generating text; it’s taking action based on that text.

What agents are used for:

- Automating development tasks like refactoring, generating files, or running commands

- Orchestrating workflows across APIs, services, and codebases

- Acting as a “developer assistant” that can plan, reason, and execute changes

- Powering AI editors (like Cursor, GitHub Copilot), CLIs, and autonomous coding environments

Here’s what this looks like in practice: you ask an agent to refactor a function, and it reads the file, traces the dependencies, updates the code, runs your tests, and fixes what broke. All from a single prompt. That’s the difference between “generate some text” and “do the thing.”

Agents are powerful, but they’re not magic. They still inherit all the limitations of LLMs: they hallucinate, they miss context, and they can confidently execute the wrong plan. The human in the loop matters more with agents because the stakes are higher. When an LLM generates bad text, you can just ignore it. When an agent runs a bad command, you might have a mess to clean up.

Prompting and Prompt Engineering

A prompt is how you communicate with an AI model. It’s the text you send, and everything about that text matters: the wording, structure, context, and constraints you provide all shape the output you get back.

Prompt engineering is the practice of crafting prompts to reliably get the results you want. It sounds fancy, but it’s really just learning what works and what doesn’t when talking to these systems.

Why does this matter?

LLMs are sensitive to how you phrase things. The same request worded differently can produce wildly different results. A vague prompt gets a vague answer. A specific, well-structured prompt gets something useful.

Common prompt engineering techniques:

- Role setting: “You are a senior C# developer reviewing this code…”

- Structured output: “Respond in JSON with the following fields…”

- Few-shot prompting: Providing examples of the input/output format you want

- Chain-of-thought: “Think through this step by step before giving your answer”

- Constraints: “Keep your response under 100 words” or “Do not include disclaimers”

How to Write Better Prompts

Be Specific

Define the task, context, format, and constraints upfront. Vague requests force the model to guess, and it often guesses wrong. Instead of “explain this code,” try “explain what this function does, focusing on the error handling logic, in 2-3 sentences.”

Provide Structure

Tell the model how to organize its response. Ask for steps, sections, bullet points, or specific formats. Structure in your prompt leads to structure in the output.

Define Done

State what the final output should look like. How long should it be? What style? What data should it include or exclude? The clearer your finish line, the better the model can aim for it.

Reduce Ambiguity

Clarify assumptions. Define how errors or edge cases should be handled. Say what the model should not do. Models will fill in gaps with their best guess, so leave fewer gaps.

I’ll be covering prompting techniques in more depth in a future post. For now, just remember: the quality of your output is directly tied to the quality of your input.

Context and Context Engineering

If prompting is how you ask, context is what you give the model to work with. Context is all the background information, examples, constraints, and reference material you provide so the model understands the task, domain, and expected output.

Context engineering is the practice of deliberately designing what information goes into a prompt. It’s about structuring background details so the model works within the right frame of reference and doesn’t have to guess.

How context is used:

- Providing relevant details (API docs, schemas, business rules) before asking for output

- Giving the model examples, definitions, or constraints to guide its reasoning

- Loading documents, codebases, or instructions into the context window

A Context Engineering Example

Compare these two prompts:

Without context:

“Write code to get the weather for a city.”

With context:

“I’m building a .NET 8 MVC app. I need to call the OpenWeatherMap API to get current weather data. My project structure is: Services/, Models/, Controllers/, Views/Weather/.

Create:

- A WeatherService class that calls the API and handles errors

- A WeatherInfo model for the response data

- A controller action GetWeather(string city) that returns the view

Use HttpClient with dependency injection. Include null checks and try-catch for the API call.”

The first prompt will get you generic code that probably won’t fit your project. The second prompt provides the tech stack, project structure, specific requirements, and coding standards. The model knows exactly what to build and where it goes.

The Context Balancing Act

Context is powerful, but it’s not free:

- Too little context forces the model to guess, leading to hallucinations or generic outputs

- Too much context can overwhelm the model, dilute the important parts, or blow through your token budget

- Irrelevant context adds noise and can actively mislead the model

Effective context management is becoming one of the most important skills in working with AI. As models get larger context windows (some now support 200K+ tokens), knowing what to include and what to leave out matters more than ever.

The Context Stack

Think about all the sources of context you might pull from for a given task:

- Documentation and API references

- Your codebase and file structure

- Error logs and bug reports

- Design specs and requirements

- Jira tickets and issue descriptions

- Agent instructions and system prompts

- Data samples and schemas

The best AI workflows deliberately curate this context rather than dumping everything in and hoping for the best.

RAG: What It Actually Is

RAG stands for Retrieval-Augmented Generation. User asks a question, system searches a knowledge base for relevant documents, those documents get added to the prompt as context, model generates an answer using that context.

RAG is useful when you’re building AI systems that need to answer questions about specific documents or data the model wasn’t trained on: customer support bots that reference your docs, internal tools that search company knowledge bases.

If you’re a consumer of AI tools rather than someone building AI systems, RAG is mostly a buzzword. When someone says their product “uses RAG,” they’re saying “we fetch relevant context and give it to the model.” That’s context engineering with an automated retrieval step. The term sounds more impressive than “we search your docs and paste the results into the prompt,” but both descriptions are accurate.

How AI Editors Work

You’ve probably used GitHub Copilot, Cursor, or similar AI-powered development tools. But how do they actually work under the hood? Understanding this helps you use them more effectively.

The basic flow:

- Collect context from your environment: the current file, nearby code, project structure, open tabs, and any files you’ve explicitly referenced

- Package that context into a prompt along with system instructions that define how the model should behave

- Send the prompt to an LLM API (OpenAI, Anthropic, etc.)

- Receive the response: code completions, diffs, explanations, fixes, or multi-step plans

- Apply changes in the editor: inline suggestions, code actions, or automated file edits

The editor is doing a lot of context engineering on your behalf. It decides what code is relevant, how to structure the prompt, and how to present the model’s output in a useful way.

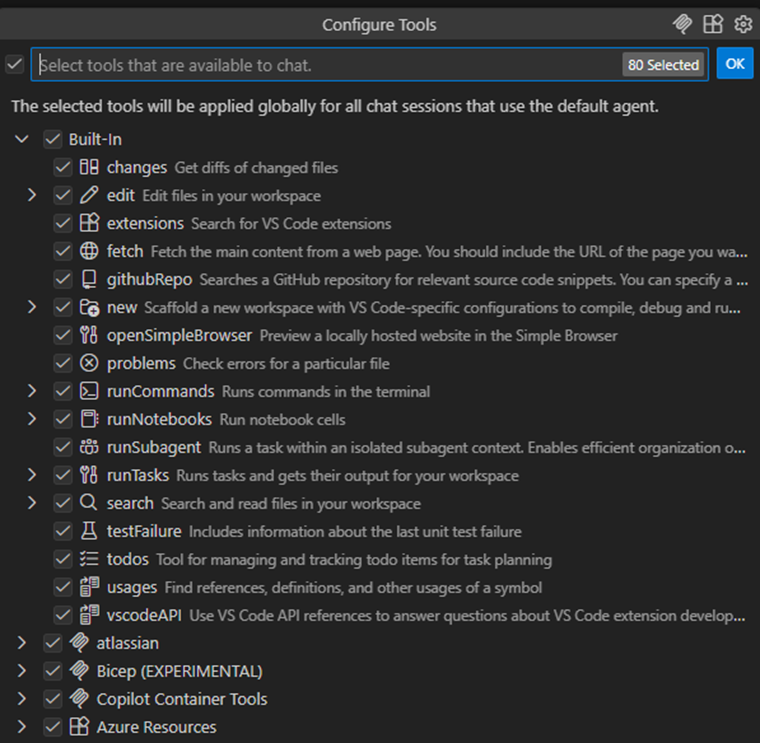

LLM Tools

Here’s where it gets interesting. Modern AI editors don’t just send prompts and display responses. They expose tools that the LLM can request to use.

The LLM doesn’t modify your code directly. Instead, it requests that the editor perform actions on its behalf: “edit this file,” “run this search,” “apply this diff,” “execute this terminal command.” The editor then decides whether to allow the action and carries it out.

Why tools matter:

- Tools provide structured inputs and outputs, not free-form text that might be malformed

- The editor enforces permissions and sandboxing for safety

- Tools enable complex workflows: refactoring across files, generating multiple files, running tests, etc.

- The LLM can chain tools together to accomplish multi-step tasks

This is what turns a chatbot into an agent. The model can reason about what needs to happen, request the right tools, observe the results, and continue until the task is done.

If you look at the screenshot, you’ll notice additional tools at the bottom. Some of these are added via MCP (Model Context Protocol) servers, which is the last topic we’ll cover in this post.

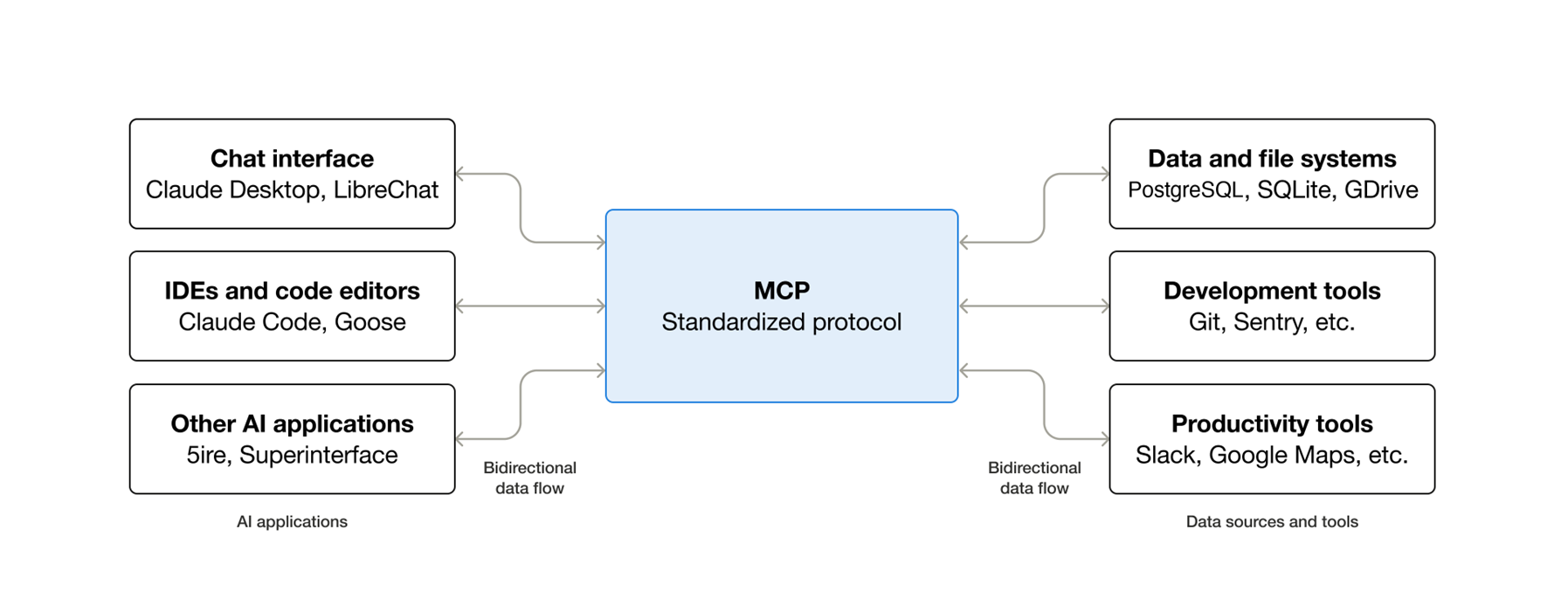

The MCP Protocol

MCP (Model Context Protocol) is an open standard, introduced by Anthropic in late 2024, that defines how LLMs communicate with external tools, data sources, and context providers. It’s since been donated to the Linux Foundation under the newly established Agentic AI Foundation, co-founded by Anthropic, Block, and OpenAI.

At its core, MCP is surprisingly simple: it’s a JSON-RPC wrapper that lets you expose tools to LLMs in a standardized way. But that simplicity is what makes it powerful. Instead of every AI tool building custom integrations, MCP creates a common language.

What MCP provides:

- A standard way for LLMs to access tools, data, and context

- A protocol that defines how models and external systems communicate safely

- Consistent behavior across different apps, agents, and platforms

How it’s used:

- Lets LLMs call tools (read files, search, run commands, query APIs)

- Allows editors and hosts to control permissions, sandboxing, and context sharing

- Enables models to execute actions through controlled, permissioned tool calls

Image source: modelcontextprotocol.io

Why MCP Matters

MCP addresses real problems:

- Reduces hallucinations by giving models direct, reliable access to real data instead of guessing

- Improves safety through permissioned, sandboxed tool calls rather than unrestricted execution

- Makes AI tools more capable by letting them integrate with your existing infrastructure

- Standardizes the ecosystem so one MCP server works across multiple AI clients

This enables the next generation of AI workflows: code execution across files, automated refactoring, API integrations, and truly autonomous agents that can interact with your actual systems.

MCP in Practice

Here’s what MCP servers look like in practice. The Atlassian MCP server, for example, exposes tools for Jira and Confluence:

With this connected, your AI editor can search Jira issues, read Confluence pages, create tickets, and add comments, all through natural language requests. The model doesn’t need to know Atlassian’s APIs. It just calls the tools the MCP server provides.

Another one I use constantly: the Azure MCP server. It lets the agent query Azure resources, check deployment status, and pull infrastructure details directly into the conversation. Instead of switching to the portal or running CLI commands, I just ask. Saves more time than you’d expect.

MCP is absolutely worth learning. If you’re building with AI or just want to extend your AI editor’s capabilities, understanding MCP will become a foundational skill. Check out modelcontextprotocol.io for the full spec and a growing list of available servers.

Wrapping Up

These are the concepts that actually matter when working with AI tools:

- Models are the trained artifacts that do the work. Different models have different strengths, and where they run (local vs remote) affects cost, privacy, and capability.

- Tokens are how LLMs see text and how you get billed. Understanding token limits and costs helps you work more efficiently.

- Agents are LLMs with tools. They can take actions, not just generate text, which makes them powerful but also higher stakes.

- Prompting is how you communicate. The quality of your output depends on the quality of your input.

- Context is what you give the model to work with. Good context engineering is becoming one of the most valuable skills in AI.

- AI editors collect context, call APIs, and apply changes on your behalf. Understanding this flow helps you use them better.

- MCP standardizes how models access tools and data, making AI tools more capable and extensible.

None of this is magic. It’s pattern matching, statistics, and good engineering. But when you understand how these pieces fit together, you can use AI tools far more effectively.

Next Time: Prompting and Context Engineering in Depth

In the next article, I’ll go deeper on prompting and context engineering with practical techniques I use daily. We’ll look at specific patterns, common mistakes, and how to get consistently better results from AI tools.

See you there.